20th June 2023

Part A: Introduction

About us

Drive Electric is a not-for-profit advocacy organisation supporting the uptake and mainstreaming of e-mobility in New Zealand as part of the effort to decarbonise transport.

Drive Electric represents a member base comprising new car OEMs and retailers, used car importers and distributors, infrastructure organisations (electricity generators, distributors and retailers, electric vehicle service equipment suppliers), e-bike/scooters, heavy vehicle importers, finance, fleet leasing and insurance companies, along with electric vehicle users. We have more than 70 members from the sector.

Our response to the draft advice

Our response relates to:

- Chapter 9 Energy and Industry

- Chapter 11 Transport

We are focused on the sections of the draft advice that relate to our mission to accelerate the uptake of e-mobility in New Zealand to support the decarbonisation transport. Our response therefore draws out what’s most relevant to that mission. We are not expressing a view on other aspects of the draft advice and this should not be interpreted in any other way than we have not commented on it.

Headline positions

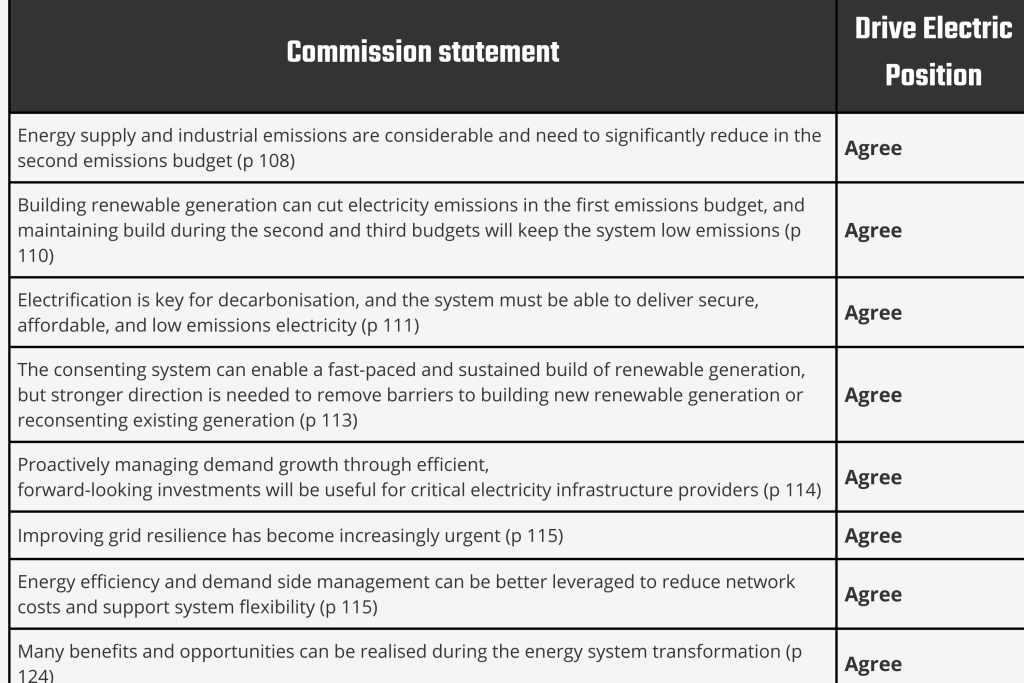

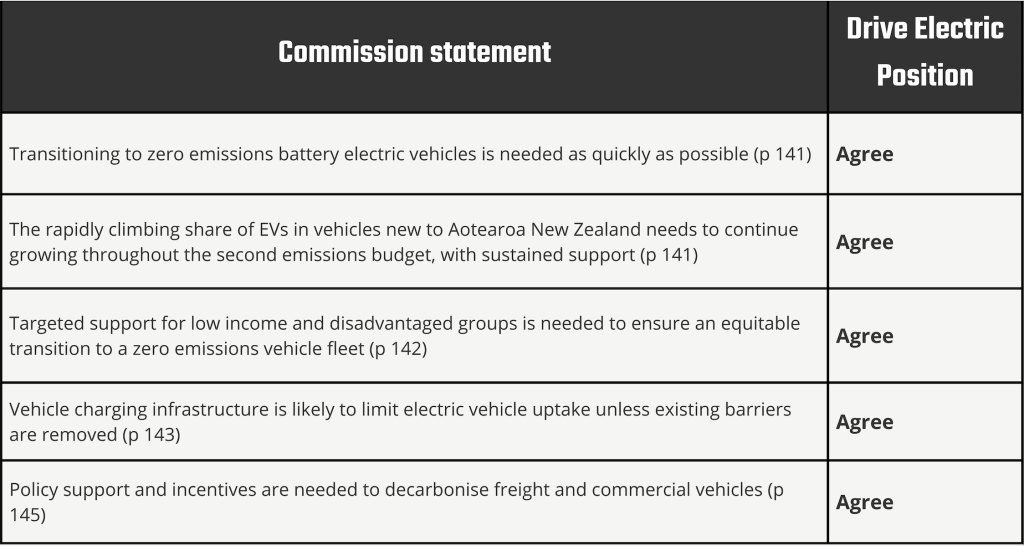

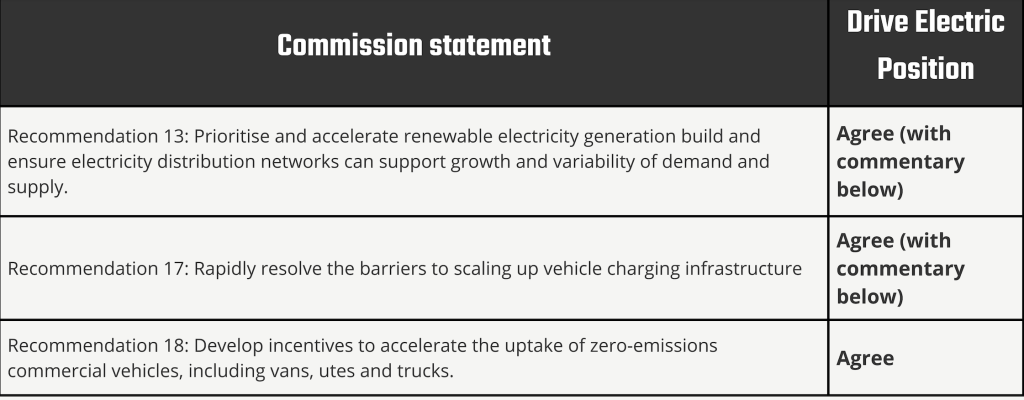

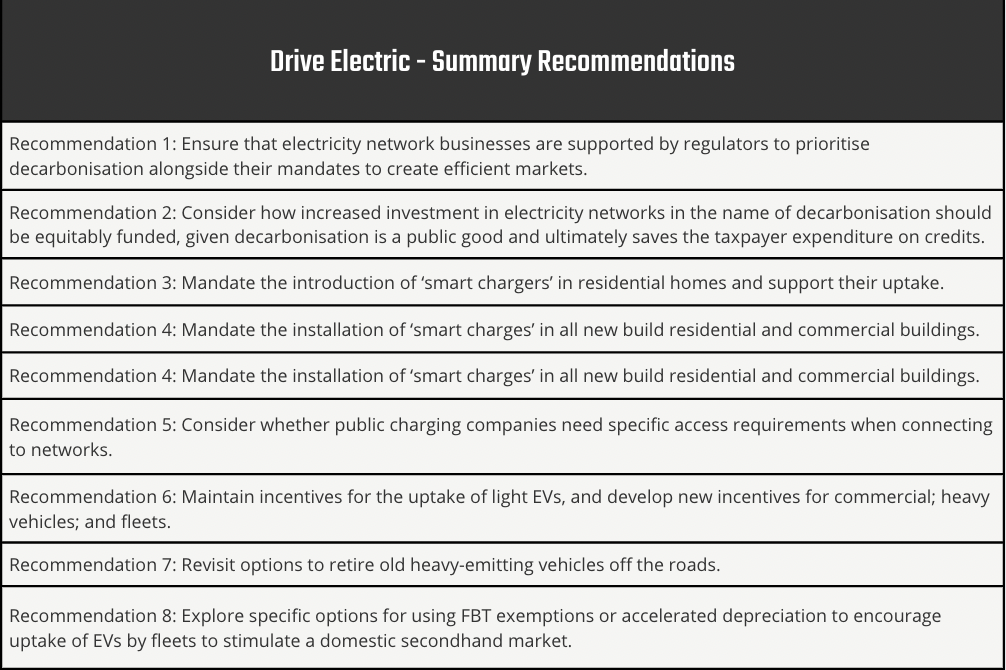

We summarise our positions in response to the draft advice’s headline statements and recommendations.

Table 1: Chapter 9 Energy and Industry

Table 2: Chapter 11 Transport

Table 3: Climate Change Commission Recommendations

Table 4: Drive Electrics Summary Recommendations

Part B: Detailed response

Introduction

New Zealand is on the cusp of the biggest transformation in transport in over a century. Over the coming decade, driven by technological advancements and requirements to decarbonise, the transport system will shift away from being powered by fossil fuels.

It is rapidly becoming clear that electric vehicles will replace petrol and diesel ICE vehicles in most use cases. International jurisdictions are setting dates for the end of new fossil fuel vehicles. Automakers are committing to dates by which they will only produce electric vehicles. The Climate Change Commission’s analysis shows that by 2030 67% of cars entering the New Zealand market are EV.

The scale of this transition cannot be underestimated. New Zealand currently has 4 million passenger cars in its fleet, the vast majority of which are fuelled by petrol and diesel. Within two decades, Drive Electric anticipates that the majority of these cars will be electric. The government itself has set a target to have 30% of the light fleet electric by 2035.

By definition this transition is not just about transport, it’s also about energy. The transition to electric vehicles depends on the availability of renewable electricity and the infrastructure to enable users to charge their vehicles.

Part B.1: Energy and Industry (Chapter 9)

We agree with the Commission’s direction in Chapter 9. We would make the following additional points:

- E-mobility, by definition, depends on affordable and reliable renewable electricity. Electricity Distribution Businesses (EDBs) are facing significant demands for new connections because of decarbonisation. This will only intensify.

- Costs associated with connecting to networks can be prohibitive for investment in public charging (more on that below in Part B.2 Transport).

- A fundamental question is emerging around who is responsible for investing in network upgrades, when these upgrades are for decarbonisation initiatives. (Or more correctly, what is a fair allocation of the costs associated with connections and any associated upgrades.)

- Commerce Commission and Electricity Authority settings must enable EDBs to invest in network infrastructure to support e-mobility uptake (and other forms of decarbonisation). Decarbonisation should form part of the mandate of the regulators, alongside efficient markets.

- There needs to be further consideration given to how to enable private investment into decarbonisation initiatives that require renewable energy and connections, but where the business case may not yet be economic, because of the cost of doing so.

Part B.2: Transport

Private charging

In New Zealand, currently 82% of charging is done at home.2 Smart charging will help make the most of New Zealand’s existing electricity infrastructure and avoid unnecessary capital investment, by helping manage peak demand. It is critical that measures are taken to support widespread adoption of ‘smart chargers’ in parallel with the adoption of Electric Vehicles (EVs).

EV smart charging could save the New Zealand economy close to $3 billion by 2035.3 It also saves people money, EECA figures show that charging at home will cost $5 at home to drive 100km, $15 using a public fast charger, and $18 using petrol.

We have provided a full submission on this matter to EECA’s Green Paper: Improving the performance of electric vehicle chargers. To summarise our views:

- Drive Electric supports the definition and regulation of ‘smart chargers’, but this needs to be done carefully

- The intent of this regulation should be to enable the creation of a demand response market in the interests of end users, in support of decarbonisation, and making cost effective investments in infrastructure.

- Drive Electric supports the exploration of a well designed government subsidy to overcome barriers to uptake of ‘smart chargers’, justified by the collective benefit of smart charging to the electricity system (including economy-wide savings) and decarbonisation.

Additionally, Drive Electric recommends that the Building Code be updated to require every new home with a dedicated parking space to install a Smart EV charger with a universal socket for all makes of electric vehicles.

It is significantly more cost effective to install charge points in new builds. Drive Electric analysis suggests that an EV charger installed in a new home will add an approximate cost of $2,000. However, if an EV charger is retrofitted this cost more than doubles. By mandating the installation of chargers in new builds, this will potentially save hundreds of millions of dollars by 2050.

Existing residential buildings undergoing “major renovation” should also be required to make the parking spaces EV-ready, with cabling routes installed to support charge points at each parking space.

New non-residential buildings and older such buildings undergoing major renovations should be required to install at least one EV charger and the cabling routes to support charge points at one in five parking spaces. Large existing non-residential buildings with more than 10 parking spaces should be required to install at least one EV charger.

To ensure the Code is sufficiently future-proofed, all EV chargers should have a minimum output power of 7 kW and must be “Smart” devices, using an open communications standard enabling demand response capability.

Public charging

To support user confidence, reduce range anxiety, and drive the uptake of EVs there is an immediate and pressing need to ensure our public charging system is built out.

Public charging gives users the confidence to adopt EV technology, and alongside the sticker price of EVs, is probably the greatest enabler of uptake. This is in part psychological and in part a necessity. Necessity stems from the need for users to charge their vehicles on long-distance travel and when away from home. Additionally, there are many users who cannot charge at home and will need to depend on public facilities. The Climate Change Commission’s 2023 Draft Advice to inform the strategic direction of the Government’s second emissions reduction plan (draft advice) says around 15% of households lack a dedicated car park, and these people will need public facilities.

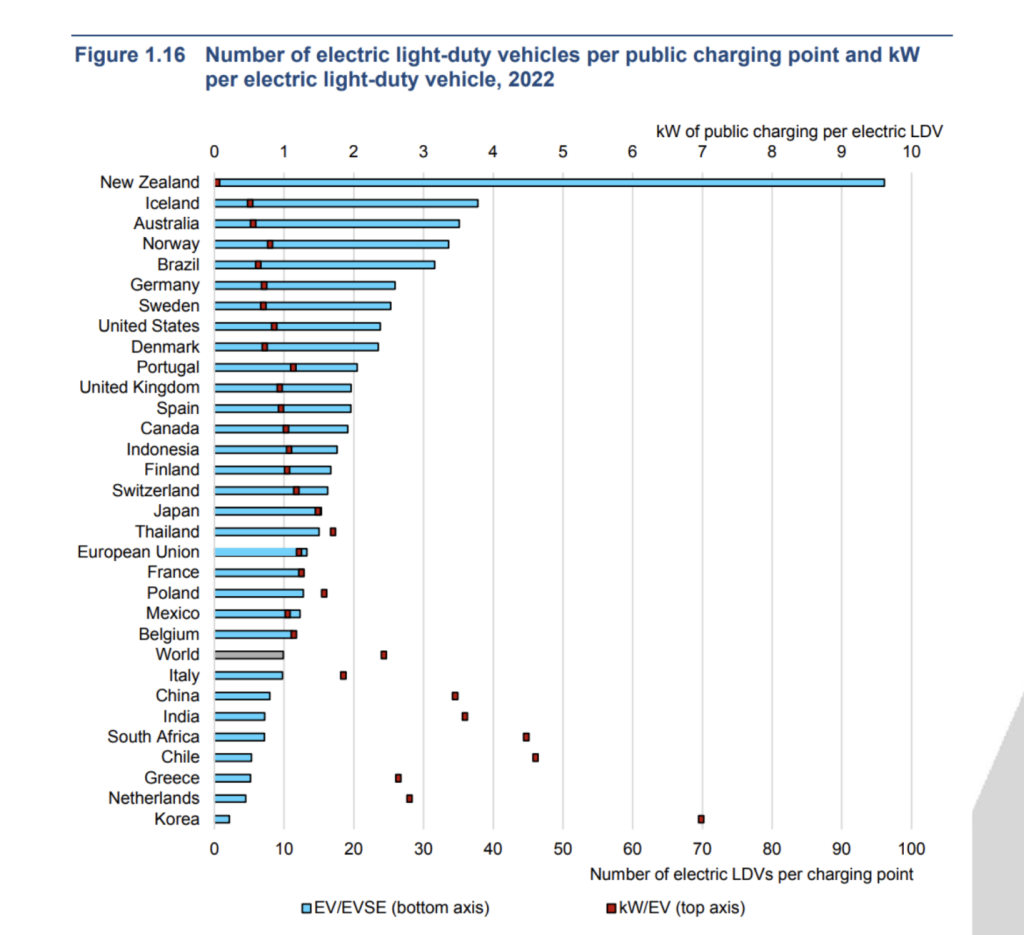

Compared to other countries, New Zealand is desperately behind in the rollout of this infrastructure. The graph below from the IEA demonstrates this.

Table 4: Number of EV per public charging point and kW per EV, 2022

Analysis from ChargeNet, a public charging operator, using Climate Change Commission data suggests that demand for public charging is estimated to increase from ~10GWh in 2023 to 690GWh in 2035. It is likely that up to $400m will need to be invested in the public charging network over the next 3-5 years.

This shortage in public charging infrastructure has been confirmed in the Climate Change Commission’s draft advice. It has specifically recommended (recommendation 17) that the government must rapidly resolve the barriers to scaling up vehicle charging infrastructure. We note this must be done well before the second emissions budget period, or we risk hampering the uptake of electric vehicles.

Public charging businesses, including Jolt, ChargeNet, Z, BP, Tesla, and Meridian, have private capital to invest in public charging in New Zealand. All of these businesses report that they have significant pipelines that are constrained. There are a range of reasons that go beyond those listed in the draft advice, relating to the costs of connecting to networks and the processes behind them.

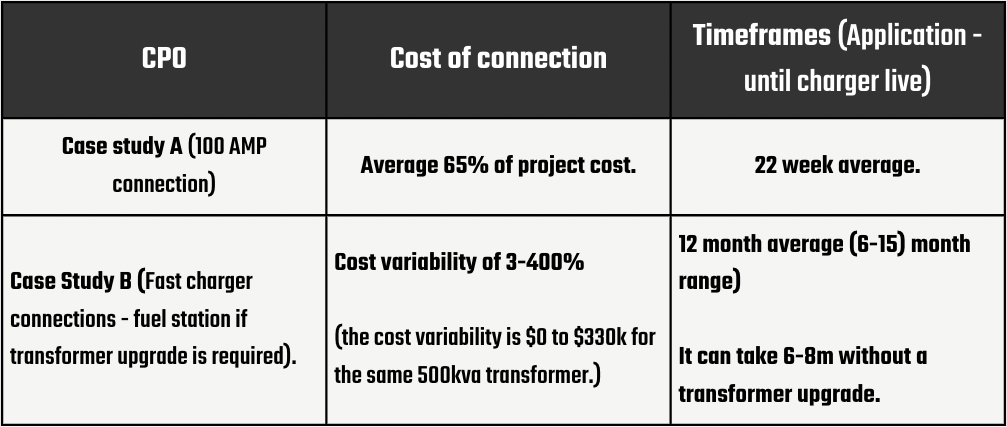

Connection costs can make it uneconomic for public chargers to invest in new infrastructure. Alternatively, these costs can slow down connections as CPOs wait for the economics to shift. Costs of connecting to the network are usually comprised of:

- capital contributions

- development contributions

- cost of equipment (e.g. transformers)

- cost of civil works

- cost of traffic management

- reinstatement costs

Additionally connections can be slowed down because of the processes associated with connecting to the network. Issues can arise from application time frames; EDB resourcing; and network transparency. Drive Electric and the ENA are currently working together on identifying improvements to process issues.

Drive Electric data from two CPO members

Charging providers say that the consequences of the current situation may be significant, and could include:

- Inability to meet consumer demand for charging;

- Regional disparities / postcode lottery;

- Dampening consumer demand in EVs; and

- Difficulty in securing a steady stream and sufficient depth of private investment.

It’s important to note that EDBs pricing policies are heavily regulated, and so there are valid reasons for these costs. The challenge becomes that as a society if we want to decarbonise how can these costs be allocated so that private sector investment is enabled.

Reasons for the current situation include:

- Commerce Commission settings encourage regulated distributors to manage cost recovery risk (and ensure costs are borne by access seekers, rather than general electricity users) by asking for up-front capital contributions.

- Electricity Authority rules that ensure fast and affordable distribution network access apply only to distributed generation. Distributors set their own terms for public charging installations. (And there are 29 EDBs with different prices and processes.)

- Distributors set requirements regarding who can carry out connection work in their network area. This limits competition and leaves access seekers as price takers. (However, this is often to ensure safety and quality of work.)

- Public chargers are allocated to ‘general’ non-residential tariff categories, rather than dedicated and fit-for-purpose smart tariff categories.

Opportunities to improve the cost of connections and process could include:

- Asking the Electricity Authority to consider whether public charging infrastructure should have:

- dedicated access regime, similar to distributed generation

- capital contribution policies that improve predictability (and consistency), e.g. through standard connection charges or other options

- a dedicated tariff category that rewards load management and addresses subsidy at a consumer group level (not individual sites).

2. Asking the Electricity Authority and the Commerce Commission to consider:

- working with distributors on broadening the eligibility of who can do connection work (including design and construction) or what equipment can be used, subject to important safety criteria.

- asking distributors to make network location information readily available to access seekers, for example through open GIS.

- asking distributors to make network capacity information available proactively, to further assist access seekers to select suitable locations.

3. Asking the Commerce Commission to consider the need for widespread decarbonisation through electrification when setting distribution sector input methodologies (IMs). IMs prescribe asset valuation, cost allocation, risk allocation (between supplier and customers) and financial return settings. (We note that IMs for 2025-2030 are being set by the end of 2024.)

(We acknowledge that both ComCom and EA are independent regulators and these requests need to be made appropriately through the right channels.)

However, there’s a real possibility that the current regulatory system for network businesses may not be fit for purpose to best enable decarbonisation through electrification. It’s possible that the electricity sector regulators may need to be given a fundamental mandate to encourage EDBs to support decarbonisation. Alternatively, the government may need to find a way to invest in the outcome of decarbonisation.

It’s also essential that local councils are engaged in the roll-out of public charging in New Zealand. They have a role to play in making sites available, both Council amenities but on-street. A key question is ensuring the incentives are right for Councils and there’s no reason why enabling EV charging cannot be a revenue opportunity for Councils.

Funding

The case remains for government investment in the roll-out of public charging. This is to address barriers to investment or market failures, particularly to ensure equity of access (e.g. in small or rural locations, tourist towns with fluctuating demand). (The government should not intervene where the private providers are willing and able to make commercially viable investments.)

This investment will need to go beyond what the existing Low Emissions Transport Fund (LETF) is designed to do, both in terms of mandate and scale. We acknowledge the recent investment in Budget 2023. More work needs to be undertaken to understand whether this investment will be sufficient.

Additionally, it is critical that this public investment is spent so that it unlocks private sector investment. Public funding support should be tied to demonstrated market gaps and long-term pathways to sustainable business models. The market can solve for the location and charging offer. In other words, public funding agencies should not be prescriptive about location and type of chargers. It is likely that relatively small government contributions can be used to unlock much larger private sector investments. In other words, it is unlikely 50/50 co-funding will be necessary.

Additionally, there may need to be public investment in the short term to build additional network capacity to ensure EV adoption and enable decarbonisation across other residential and commercial energy users. This is particularly the case if other mechanisms will not address barriers relating to network connections within the next 6-12 months.

Zero emissions vehicles uptake

Drive Electric supports the continuation of the incentives for light vehicles and emissions standards. Since June 2021, the average emissions of newly registered vehicles in New Zealand have dropped 21%. Over their lifetimes, vehicles already bought in under this Clean Car Discount will save 2 million tons of emissions (through to March 2023).9

We suspect that incentives for light vehicles will only be required for a discrete period of time, until EVs hit price parity with the sticker price. Adoption rates are another factor to consider, which may even allow the incentive to come away before price parity has been hit, because of the compelling total cost of ownership.

We understand why the government is pursuing a fiscally neutral scheme (Clean Car Discount) through the fees on high emissions vehicles, but using other sources of funding may be perceived to be more equitable – such as revenue from the ETS. (In this way emissions pricing on petrol is being used to encourage EV uptake.)

The original government cabinet paper10 showed that the original Clean Car Discount is an efficient investment in emissions reduction:

Fully funded, the incremental cumulative impact of the Clean Car Discount from 2022 to 2050 is a reduction of between 2.6 and 9.2 mega tonnes of CO2. The marginal abatement cost (MAC) per tonne of CO2 ranges from -$170 to -$199. This means it would save the economy money rather than place costs on it. This is primarily due to the significantly reduced ongoing fuel costs that New Zealanders would pay by being able to afford to buy a zero or low emission vehicle through this policy. This makes the Clean Car Discount an effective and economically efficient policy to reduce emissions.

In addition to incentives for light vehicles, other tools could be used to specifically encourage fleets to quickly migrate to EVs, either through accelerating depreciation or removing FBT. Fleet companies purchase at least 24 per cent11 of vehicles in New Zealand, and these vehicles spend between 1 and 5 years in fleets. This is the quickest way to get more New Zealand-new, secondhand EVs onto the market. Growing a secondhand market is an essential way to achieve more equitable access to e-mobility.

It would be useful to explore the Australian experience of removing FBT as an informative approach. One fleet operator has said that their Australian business has experienced an increase of quote volumes for BEV leases increasing almost 800%.

Additionally, with the end of the existing Clean Car Upgrade scheme, the government should reconsider how to incentivise the removal of older emitting vehicles from the roads – in an economically efficient way.

Finally, we support a well designed short-term incentive to encourage the uptake of commercial and heavy electric vehicles. Vehicle owners are unlikely to make these investments until they are economic. However, there is a public interest in accelerating these decisions and getting these vehicles on the roads sooner.