Last September, a crowd gathered in a carpark in rural Nebbenes, 60 kilometres north of Oslo, to witness a milestone in Norway’s electric vehicle revolution. The occasion was the grand opening of the world’s largest EV fast-charging station, capable of charging as many as 28 vehicles at one time, of all makes and models.

If anyone was watching from New Zealand, the scenario must have seemed improbably futuristic, a brave new world in which EVs pull into gas station-like charging facilities, to ‘fill up’ alongside dozens of cars just like them. In this country, as of the start of April 2017 there were 3120 electric vehicles on our roads, and an estimated 90 per cent of charging is done at home and overnight, using AC power.

But the rollout of fast-charging infrastructure is happening here – in fact, there are more fast-chargers than in Australia, and that number is growing weekly. Meantime, local authorities in places such as Wellington are exploring providing on-street charging, while fleet owners and individuals who are weighing up going electric ponder their various charging options.

Poised at this pivotal stage, and with significant developments in both vehicle and charging technology imminent, some questions need answering.

What, for example, is happening overseas in the development of charging infrastructure, and what can we learn from it? What are the drivers for technology selection, and what are the pros and cons of the different charging technologies? What role can public fast-charge infrastructure play in encouraging the uptake of EVs? And what should you know about charging options before you switch to electric?

THE GLOBAL PICTURE

Europe is grabbing the attention when it comes to the rollout of EV charging infrastructure. Last year, the EU issued a draft directive that would require every new or refurbished house in the EU zone to have an EV recharging port. The directive also mandated for 10 per cent of parking spaces in new buildings to have recharging facilities by 2023.

Norway (not an EU member) and the Netherlands are leading the charge in Europe. Both have committed to phasing out diesel engines by 2025, while Norway in particular has established a world-leading position on EV uptake, with one third of new vehicles now electric.

Much of that success can be put down to tax breaks and other incentives for EV owners, but Norway and the Netherlands have also recognised the catalysing effect of building a strong public network of charging infrastructure.

Much of that success can be put down to tax breaks and other incentives for EV owners, but Norway and the Netherlands have also recognised the catalysing effect of building a strong public network of charging infrastructure.

In the Netherlands, the rollout has been driven by both private commercial interests and public organisations, the latter including regional governments and individual cities.

On the commercial side, Dutch outfit Fastned has to date installed 59 of an intended 200 fast-charging stations, drawing on solar power from the stations’ canopied roofs, plus wind-generated power from a third party.

Fastned customers sign up to monthly plans, and buy on demand using a Fastned app. It’s simple and seamless, a feature more generally of the Dutch charging scene, where there is a national agreement to promote interoperability.

Kumail Rashid, National Sales Manager – Power Conversion at ABB, believes the Netherlands example is highly relevant to this country, not least because the government there, like here, is less hands-on than somewhere like Norway.

Rashid notes that the first Fastned stations, installed two-and-a-half years ago, are now breaking even – an encouraging sign. He also sees a lesson in Fastned provisioning its stations to be easily upgraded from two to four chargers, future-proofing them for a time when burgeoning EV ownership might otherwise lead to queues.

“The Netherlands is a great example of where infrastructure is driving uptake,” he says.

As for Norway, it demands attention simply because of the sheer scale of uptake, with 135,000-plus plug-in vehicles on the roads, or more than one in every 100 passenger cars. The rollout of fast-charging infrastructure has been less startling, but there is a goal to have a charger every 50 kilometres, and the couple of hundred stations already deployed have served the purpose of easing ‘range anxiety’.

One aspect of the Norwegian story that bears highlighting relates to AC standard charging. As in other European countries, garaging in Norway is scarce, and municipal governments have responded by providing streetside AC charging for parkers.

ChargeNet CEO Steve West sees relevance here for a city such as Wellington, which suffers from a relative dearth of garaging. “That is a challenge for New Zealand: how do we provide charging for EVs in Wellington if people don’t have offstreet parking?”

THE HOME FRONT: WHERE IS NEW ZEALAND AT?

Leaving Wellington aside, most kiwi EV owners will be able to charge at home with very little hassle. Typically, the common 10 amp socket is sufficient, providing roughly ten kilometres of range for every hour the car is charging. (The rule of thumb is that for every amp of charge current you can expect one kilometre of range.) Some owners get rewiring to achieve 15 or 32 amps, but either way, most people will charge their cars overnight, like a cellphone. Given that New Zealand cars travel a daily average of 40 kilometres, that’s generally more than sufficient, most of the time.

Meantime, however, a network of public AC and rapid DC charging stations is taking shape, spearheaded by ChargeNet NZ, ABB (as a technology supplier), and Vector, with several other lines companies playing a lesser hand. There are 80-odd fast charging stations deployed, ranging from Kawakawa in the north, to Invercargill.

So far, the rollout has unfolded largely organically, but in the context of a government target of 64,000 EVs driving our roads by 2021. More recently, the NZTA has stated its vision of “enabling a nationwide network of public charging infrastructure so that electric vehicle drivers can confidently roam New Zealand’s state highways”.

Among other things, that NZTA document recommends investors take a ‘journey focus’ that prioritises charging infrastructure along national, regional and arterial roads. It also set some goals, including having DC fast charging stations every 75km along national, regional and arterial state highways, AC charging every 50km, as well as AC stations every 50km along primary and secondary collector routes.

Local government is also beginning to get involved. In April, the Wellington City Council announced plans to convert up to 100 car parking spaces for the exclusive use of car-sharing and electric vehicles. Of 37 bays so far selected, 10 will be allocated for medium-speed chargers and three for fast charging.

It’s an evolving scene, in other words, with potential for parties such as big box retailers and supermarkets to get involved. Right now, however, who are the major players in the rollout, and what are they offering?

It’s very much a developing field, the commercial landscape unsettled. Whether charging will emerge as a wholely contestable industry remains unclear, and that tension is being played out in various ways, right down to how public charging stations are legally defined. Powerco Commercial Manager Eric Pellicer says Powerco’s position is that EV charging sites are the petrol stations of the future. “We feel this area is highly contestable and we’re more than happy to be a supplier to these installations, not a provider.”

While these issues are being debated, logistical challenges to the rollout have emerged – most significantly, a reluctance among landowners to host EV charging sites. In response, both Vector and ChargeNet are partnering with organisations with multiple sites such as McDonalds and Foodstuffs, while ChargeNet has often had to rely on territorial authorities. Either way, the process is seldom quick.

Nevertheless, there’s an expectation that the national network of fast-charging stations will top 150 within the next couple of years. That’s a surprisingly comprehensive rollout, given the still low numbers of EVs using our roads, and it’s even more striking because some of these chargers are going in at provincial sites with no critical mass of population.

The reasoning is a variation of the ‘build it and they will come’ idea. If you want to stimulate the mainstream to go electric, you have to ease people’s range anxiety by providing assurance they will never be short of a charge. (According to some studies, consumer concern about driving range is second only to price as a barrier to purchasing an EV.)

The belief that the availability of fast-charging is critical to driving EV uptake is not necessarily borne out everywhere – Norway is one notable exception. But in places such as Japan, which has dabbled in EVs since the 1990s, uptake was absolutely invigorated by the advent of significant charging infrastructure.

When people talk about range anxiety and the ability to travel between cities, fast charging is a huge enabler,” says ABB’s Rashid. “In Europe, charging stations have to be 50-100 kilometres apart, and once that comes in, you reach a tipping point. People might not even necessarily use a charger, but from our perspective, having it available is a psychological requirement.

Technology: What are the drivers?

Versatility

As mentioned, New Zealand’s charging infrastructure has so far developed with minimal involvement by government. On the face of it, the hands-off approach appears to have been successful, but there have been some growing pains – notably, around the issue of connector types.

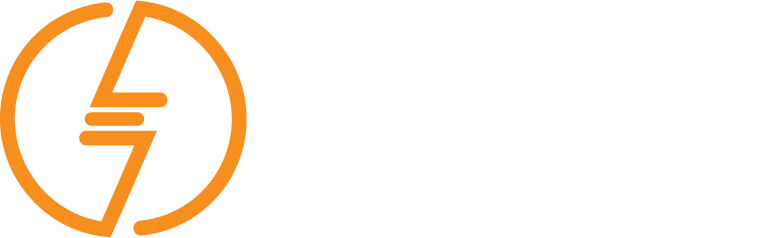

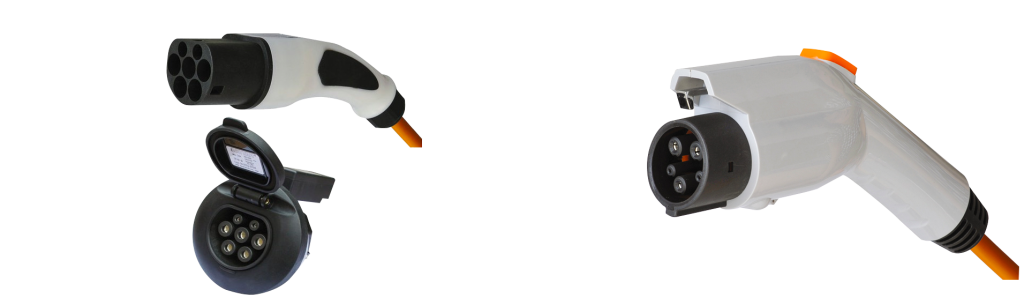

At the moment, ChargeNet, the various utility companies involved in EV charging and vehicle suppliers such as BMW are in the throes of changing over their plug types, from Type 1 to Type 2, at their own expense. The retrofit was made necessary when, having left it to the market to decide, the NZTA belatedly announced a recommended EV charging standard.

Despite the hassle and expense, all the parties involved have welcomed the decision to upgrade to Type 2, which is standard in Europe and far more versatile. (Type 2 charging stations can service both types, so long as drivers carry the correct lead.)

ChargeNet’s Steve West says making socketed Type 2 the standard is the smart move. And he has some advice for fleet owners on the subject.

“Even if you were starting off in electric vehicles with a fleet of Type 1 delivery vans, it would still make sense to go for Type 2 socketed chargers,” he says. “You’d just buy a bunch of Type 2-to-Type 1 leads, and plug them all in and leave them. For all intents and purposes it would behave exactly as a Type 1 tethered charger, but when you eventually bought a Type 2 vehicle you could simply unplug that cord.”

Type 2 is also a much cleaner solution for streetside charging than Type 1, which requires an attached cable. “You can easily imagine a street sweeper snagging on one of those cables, and the mess that would make. With socketed Type 2 there is no issue of tethered cables getting in the way.”

The story of plug types neatly illustrates one of the unique challenges New Zealand faces when it comes to technology selection. As a nation, we tend to buy mostly second-hand cars, imported from diverse territories. In this case, because our earliest EV imports were predominantly Japanese, we ended up with Type 1 as a defacto standard, even though it’s not particularly appropriate for this country.

Our EV market will continue to be characterised by a plethora of second-hand makes and models, and a diversity of standards. As a result, versatility is a critical consideration for selecting charging technology.

ABB New Zealand Managing Director Ewan Morris stresses that to encourage EV uptake, the charging experience needs to be as easy and convenient as possible.

“From ABB’s point of view, it’s about multi-standard. If you’re going to invest in this equipment, and you’re typically putting it in some valuable real estate, you want that device to be as versatile as possible, so it can charge as many brands as possible.”

SPEED OF CHARGE

For most of us, our experience of charging our EVs is likely to develop a familiar rhythm: low and slow overnight AC charging in the garage or at work, punctuated by the occasional rapid DC charge for longer journeys.

Yet if EV ownership is to go mainstream, there is a ‘need for speed’. Early adopters may be happy to wait 20 or 30 minutes at a public charge point – incidentally, that charge time has strongly influenced the choice of locations, with stations generally sited close to cafes, shops and other time-killing facilities – but most of us will demand an experience more akin to that of the quick petrol station top-up. In fact, manufacturers working on the next generation of EVs are reportedly targeting a five-minute charge time.

The speed question has obvious implications for someone like a fleet owner pondering choices of charging technology (to be addressed later in this paper). But it’s also highly relevant to the roll-out of public charging infrastructure.

If New Zealand cities were to provide streetside charging for EV owners, for example, would low and slow be enough?

Ewan Morris doubts it. “In Europe you see quite a lot of standard or slow-charging AC connector points in downtown areas. Nice idea, but what they’ve realised is that you have a car sitting there for four to six hours charging, and that’s not great because you’re not getting value out of that space.”

His colleague Kumail Rashid has looked at overseas use of 11 and 22kW AC charging posts. He sees an argument for shopping malls and the like to provide them, offering their customers a small battery top-up as a perk of patronage. But it makes far less sense for infrastructure operators.

Yes, the AC charging equipment is much cheaper than DC, he concedes, but the operators still have to invest heavily in capital works and installation, maintenance costs and so on.

“And what are we trying to achieve here?,” he says. “It’s not really serving the purpose of ‘I need to get more range’; it’s more about opportunity charging. Operators are finding it doesn’t make sense. The business of providing public infrastructure to enable travel and EV uptake is not valid for 11 and 22 kilowatt AC charging.”

Another aspect of the speed question is queue time. Currently, ‘waiting at the pump’ is not an issue here, but as EV ownership climbs it may become one.

What we’re seeing from different countries, is that it’s not just about getting more chargers and more sites, but also more chargers per site,” says Rashid. “If you look at what Vector has done in Auckland, all but one of their sites have two chargers. That’s future proofing, because you don’t want to have to be waiting 15 minutes for someone else to charge.

INTEROPERABILITY AND CONNECTIVITY

For the New Zealand EV charging scene, Europe is a source of inspiration, but also of cautionary tales.

“They have hundreds of charging networks and it can be incredibly painful driving an EV across Europe for just that reason,” says West. “We don’t have that problem of driving between countries, but if we’re not careful we could easily end up with multiple charging networks and forcing people to carry multiple fobs, or at the very least run multiple apps and have multiple memberships with multiple accounts. We really want to be careful we don’t end up making it difficult here for drivers.”

The relevant analogy is of banks. Like an ANZ customer withdrawing cash from a Westpac ATM, a ChargeNet subscriber should be able to charge their car at a competitor’s station without missing a beat. Currently ChargeNet has the territory to themselves, notes West. “But if another network were to arise, we’d go out of our way to make it easy for people to roam between us.”

What’s the future of billing in that scenario? Ewan Morris says ABB is working on a payment terminal solution, but he sees it as an intermediate step. “The future will be phone apps. ABB customers in other countries have those already.”

The key to unlocking all of this depends on credible back-end connectivity, which allows an operator to monitor and upgrade their network of chargers, provide assistance to drivers, and, of course, get paid.

In ABB’s case, its rapid chargers use Microsoft’s ‘Azure’ cloud platform, enabling it to remotely support all of its installations and upgrade software. As an example of the kind of data that can be collected, ABB knows that as of February this year, its 30 New Zealand chargers delivered 127 megawatt hours of energy, via 18,000 charging sessions, equivalent to 750,000 kilometres of range.

In addition, ABB customers can, if they wish, use an ‘out of the box’ solution to monitor the performance of their charging fleet, while ABB also offers OCPP (Open Charge Point Protocol) on its stations. Vector has taken advantage of OCPP to interface to its mobile app, arming EV drivers with live status information about its network of chargers around Auckland.

ChargeNet also uses OCPP, which has become industry standard throughout the world, among other reasons because it allows charging stations and management systems from different vendors to communicate with each other. (Unison, for example, uses OCPP to connect its ABB-supplied chargers to the ChargeNet billing system.)

“If I had to give only one piece of advice to someone putting in charging infrastructure it would be to make sure that it is internet connected,” says Steve West. “That is essential, and there are so many benefits that flow from that.

“If you’re a fleet operator, for example, you probably want access control on your chargers, and the most flexible way of accomplishing that is to have them connected to some sort of management system through the Internet. If you’re a gated community and you want to provide chargers for your residents, then you need people to pay their way, and the only way to do that is to have it connected to the Internet. Or if you want to track usage, and to know which of your vehicles is using the energy, then you need to be collecting that data through some sort of system.”

He advises staying well steer clear of proprietary systems, because of the risk of the supplier going out of business. “If that happens, then you’re left with a charger you can’t use.”

FUTURE PROOFING: WHERE IS EV TECHNOLOGY HEADING, AND WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS?

The holy grail has been defined: more powerful batteries, at a lower price; long-range vehicles; high-powered, quick-turnaround charging.

That future is closer than you might think. Batteries are developing rapidly, even as the price drops. And car makers keep upping the ante: witness the Porsche Mission E, expected to go into production in 2019 with a range of 500km-plus, or the latest Tesla Model S, which is in the same ballpark.

What does that scenario mean for charging hardware? Simple: it will have to keep pace. If you have a battery three times larger, and you don’t want to spend three times longer charging it, you’ll need a more powerful charger.

In the US, the first 150kW chargers are being trialled, and the Evgo charging network recently broke ground on a 350kW charging station in California, despite the fact there’s still no production model vehicle on the market capable of charging at 350kW. Meanwhile, BMW, Ford, VW and Daimler have agreed to form a joint venture to build a network of ‘ultra-fast’ 350kW charging sites across Europe.

The advent of such powerful charging in New Zealand would be a gamechanger, and not only in terms of uptake. The criteria for locating stations, for example, would be quite different. As West remarks, 50kW is not hard to find. But if the goal is 350kW for multiple chargers, you’re no longer looking for spare capacity, but designing an installation that requires its own transformer and connection to the grid.

“It would be utter madness to do that here today,” he says, adding that the immediate task is to build a 50kW network extensive enough to enable long distance travel.

Longer term, however, an upgrade is on the cards. “With the next generation of 150-350kW chargers and cars imminent, our vision is to create stations across New Zealand like the one in Nebbenes, Norway.”

As for the emergence of long-ranging EVs, that trend will also eventually usher in changes. When vehicles can drive 400 kilometres on one charge, public charging stations can be spaced further apart. We could well be looking at a future of high-power charging corridors, with a greater number of chargers per site, and charge times approaching five minutes.

GOING ELECTRIC: WHAT DO YOU NEED TO CONSIDER BEFORE YOU MAKE THAT SWITCH?

In October last year, Mercury Energy boss Fraser Whineray and his Air New Zealand and Westpac counterparts, Christopher Luxon and David McLean, convened a breakfast meeting of 30 CEOs from some of New Zealand’s largest organisations to discuss fleet transition. (Drive Electric’s presence was felt at the meeting, with board member and Westpac head of Asset Finance Gary Nalder attending, along with a representative from Powerco.)

By the end of breakfast, all had committed to transitioning at least 30 per cent of their fleets to plug-in EVs. The two instigators, however, were already a step ahead: three quarters of Air New Zealand’s ground fleet is plug-in electric, while Mercury is aiming for a similar ratio by 2018. (Vector, meanwhile, has begun replacing all of its Auckland head office fleet with EVs, and is looking to replicate the transition at other locations.)

If you’re a fleet owner pondering making the same transition, some hard thinking is required. In the first instance, you need to fully understand the business case, because going electric requires a significantly greater upfront investment than buying non-electric.

Look at the total cost of ownership, and ask yourself what are your business objectives? The answer will steer you broadly in the direction of the type of car and ownership structure you need. Leasing is always an option.

Having made a commitment to go electric, what are the considerations? As discussed, there are some fundamental requirements for charging options. Interoperability and connectivity are critical. Multi-standard is key. Proprietary systems carry the risk of cutting down your future options, and your charging system should be compatible with the widest range of vehicle models. Type 2 is favoured over Type 1.

However, if staff are simply driving between home and work, or between offices in the same city, then a small vehicle with a 50-100 kilometre range is perfect. Rule of thumb: make sure whatever you invest in is fit for purpose.

Look at your vehicles’ typical ‘dwell times’. Do they usually do a morning run, then sit idle at work for a couple of hours? Will that be enough time to replenish the battery for the rest of the day? If not, you may need to consider investing in a fast-charge solution.

Thankfully, there are smaller, cheaper alternatives to 50kW chargers, including 25kW DC wall boxes that can typically be used without needing any exotic wiring. In addition, a 12kW option is likely to hit the market later this year. (As a general rule, 50kW gives you 250 kilometres range for an hour’s worth of charging; 25kW delivers 125km; and 12kW, roughly 60km.)

However, if a business can mount a case that it needs fast-charging, then buying hybrids should also be considered.

Another issue is onsite infrastructure. “A fleet owner thinking about converting 10 or 20 cars over to electric really needs to consider what they need to have on-site to accommodate those cars,” says Powerco’s Eric Pellicer.

He stresses that over time, electric vehicles deliver large savings in total cost of fleet ownership. “However, if you install 10 AC chargers, that’s like installing 10 industrial fridges on your property; it will have a material impact on your power bill and the configuration of electricity on your site.

“Giving consideration to those things is important. Where do you put the charging infrastructure? Who’s going to be accessing it? How much is it going cost you? People focus on the cars, but they also need to think about the ecosystem.”

On that point, also ponder carefully where to site chargers. Drilling down further, how do you decide between DC fast-charging and standard AC? And how do you choose the most appropriate electric vehicle?

Start by acquiring a thorough understanding of exactly how your current fleet is operated. Use a phone app, or reset the trip counter every morning, and over a fortnight gather data on how far your cars travel every day.

Does your fleet-driving workforce include salespeople and others who need to regularly make long inter-city trips? If so, it makes no sense to put them in a low-range Nissan Leaf, because the charging infrastructure isn’t there yet to support it.

According to the US-based Edison Electric Institute, there is potential to offset the cost of installation by placing charge points where they can be dual-purposed. During the day, staff who own electric vehicles and members of the public can charge their EVs for a price, while at night, you use the chargers to replenish your fleet. (See the EEI’s document ‘Electric Transportation’ at www.eei.org/issuesandpolicy/electrictransportation/FleetVehicles/Documents/EEI_UtilityFleetsLeadingTheCharge.pdf)

Finally, fleet owners will need a plan to reimburse for at-home charging, mitigating the temptation for employees with company vehicles to leave charging until at work.

Matt Philp – Author

Matt Philp began his feature writing career at the New Zealand Listener, and was a senior writer for Metro, The Press and North & South. Now a freelancer, he writes on architecture, lifestyle, business, heritage and travel for several New Zealand magazines.